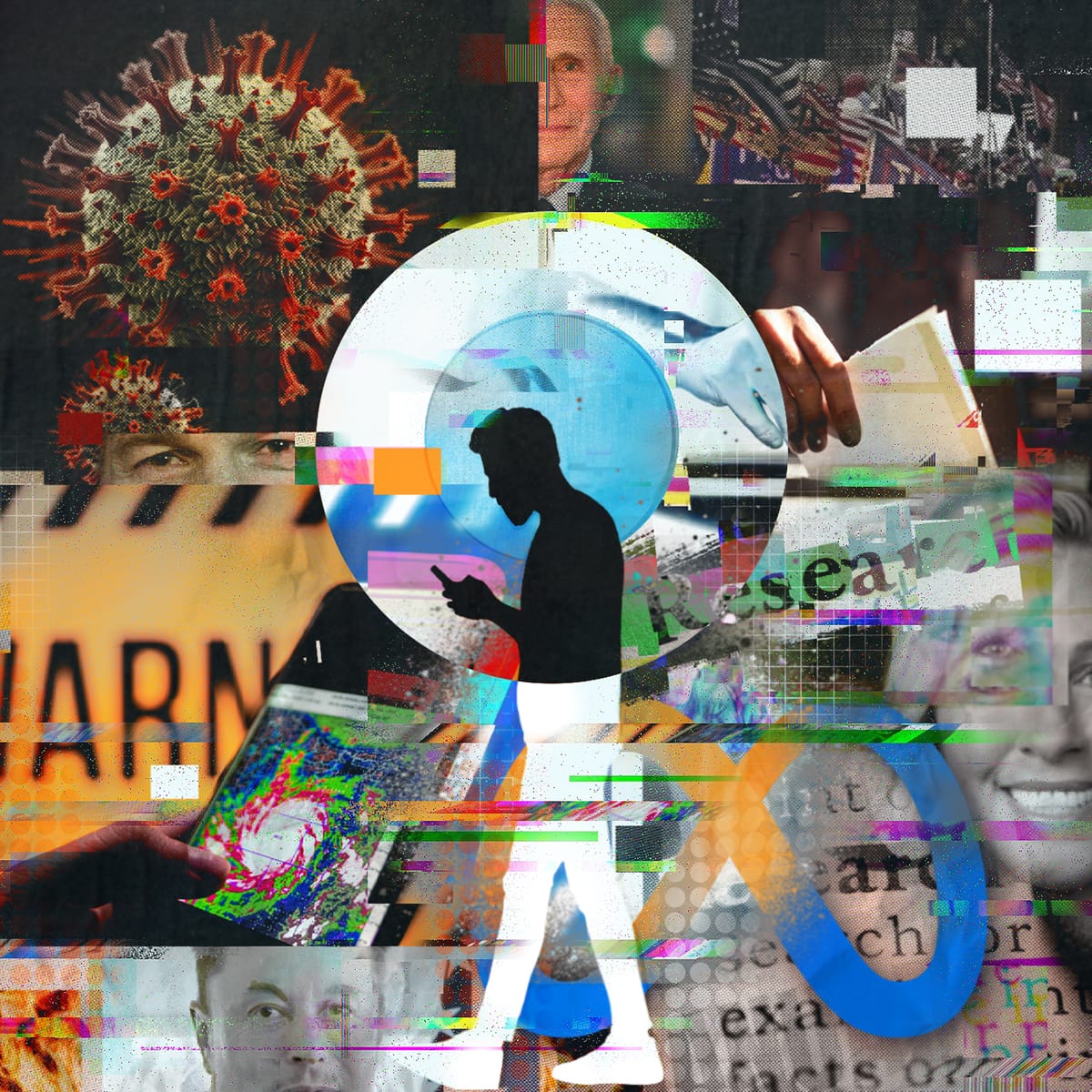

Tech researchers wanted to protect democracy. Now, they're facing lawsuits, recrimination and threats.

A rising tide of legal threats against misinformation researchers is having a chilling effect on the field—and threatening a key tool for accountability.

By Ellery Roberts Biddle | Contributor

When federal officials tapped Nina Jankowicz to help protect Americans’ security in the face of online threats, she stepped up without hesitation. The acclaimed technology researcher and Russia expert had spent years studying the consequences of online political propaganda. She knew just how harmful it can be, especially in the wake of the “Big Lie” and the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol. So at the beginning of April 2022, Jankowicz signed on to lead the Department of Homeland Security’s Disinformation Governance Board.

But by the time she was sworn in, Jankowicz had become the target of what she normally studied: a ruthless, politically motivated campaign of disinformation about her work and her personal life.

The board was intended to help state agencies better mitigate the effects of false information related to border security, human trafficking and threats of domestic terrorism. But right-wing lawmakers and media personalities accused the Biden administration of something entirely different.

Figures like Matt Gaetz and Tucker Carlson called the new board a “Ministry of Truth.” They charged that the new agency was part of a wide-scale campaign of information control by the Biden administration. Jankowicz became the target of thousands of social media messages in which people harassed her, sometimes threatening to kill, rape or otherwise harm her.

Explaining the board’s true purpose was no use. Jankowicz says her public statements about the board were “completely stripped of all nuance and made out to be something that they weren’t.”

“No amount of fact-checking and no amount of pushback” was going to help, she says. “Nothing was going to work.”

Amid the political fallout, she resigned. By August 2022, just four months after its launch, DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas terminated the board altogether.

But that wasn’t all. Before she stepped down, Jankowicz was sued by the attorneys general of Louisiana and Missouri; Jill Hines, who co-leads the anti-vax organization Health Freedom Louisiana; and Jim Hoft, owner of far-right website The Gateway Pundit. Along with Anthony Fauci, Surgeon General Vivek Murthy and dozens of other Biden administration officials, Jankowicz was accused of pressuring social media companies to remove conservative content from their platforms. Missouri Attorney General Andrew Bailey described the defendants' alleged actions as “the biggest violation of the First Amendment in our nation’s history.”

The suit was triggered by Biden administration officials’ efforts to stop the spread of digital disinformation about Covid-19. But in the eyes of key GOP leaders, their real motive wasn’t to protect public health—it was to silence right-leaning political speech.

Jankowicz was soon in good company. Hines and Hoft filed a parallel lawsuit against leading researchers who had tracked the spread of online misinformation about the Covid-19 pandemic and the 2020 election. Similar suits followed in Texas and Florida.

By late 2023, across the country, dozens of other academics and independent researchers studying digital disinformation were facing unprecedented legal threats and political scrutiny.

These attacks have left academics struggling to maintain institutional support for their work and fearful of political retribution for their research. The topic even made it onto the vice presidential debate stage, with candidate JD Vance decrying “big technology companies silencing their fellow citizens” while alleging that Kamala Harris wants to “censor people who engage in misinformation.” At the same time, big technology companies are backpedaling on their past commitments to rein in disinformation and hate speech online. With another highly contentious general election just weeks away, the stakes for the work of these technology researchers—and American democracy—feel higher than ever.

As some researchers shift course in search of safer pastures and others grapple with the loss of institutional support, the American public is at risk of losing a key tool of democracy for holding platforms and political leaders accountable to the public interest.

Academic Researchers in the Crosshairs

Right-wing politicians have long accused social media platforms of deliberately restricting conservative views, an idea that has never been proven with hard evidence. One driver of that accusation is evidence that violent speech and disinformation, the type of content that often violates social media companies’ terms and conditions, tend to be more prevalent on the political right.

Those accusations have gone from mostly rhetorical ones to congressional probes and lawsuits by figures on the right. Last summer, House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jim Jordan launched an investigation into the issue, focusing on grantees of the National Science Foundation, whom he accused of colluding with tech companies to censor online speech “at scale.” At a March 2023 hearing, Jordan derided what he called a “marriage of big government, big tech [and] big academia” that was “attacking American citizens’ first amendment liberties.”

Around the same time, the Stanford Internet Observatory—which in mid-2020 had become instrumental in helping the public understand the spread of misinformation around the Covid-19 virus—also came under attack.

In their lawsuit targeting researchers at Stanford, the University of Washington, the Atlantic Council and a handful of other technology-focused initiatives, the plaintiffs, the aforementioned Jill Hines and Jim Hoft, cited the researchers’ work on vaccine and election related misinformation and disinformation. The plaintiffs, both of whom rely heavily on social media to spread their messages, alleged that researchers had colluded with tech platforms to “monitor and censor disfavored speakers and content.”

One thing these investigations and lawfare have in common, according to Renée DiResta, who headed up much of the work at Stanford, is that “they’re led by people who rejected the results of the free and fair 2020 election.” And one reason misinformation and disinformation research has become a target, as two leading researchers noted in an op-ed in the journal Science, is that it can “blunt ideological campaigns to mislead the public."

This work has not only provided much-needed scrutiny of tech platforms, but it also puts a check on government actors spreading false narratives.

“What scares me the most is that we can’t even tell how our democracy might be eroding, because we cannot do some of this work that we used to be able to do,” says Karrie Karahalios, a leading computer science professor at the University of Illinois who has studied bias in algorithms for more than a decade. “It’s hard when you have to fear being discredited by the government that you’re trying to protect.”

“When we first started in this line of work, it was mostly companies that we feared,” Karahalios says. But facing threats from the government, she says, feels “significantly different.”

Meta, X, and other Social Media Giants Are Scaling Back Trust and Safety Efforts

For more than a decade, companies like Meta have been known to serve up everything from negative PR to cease-and-desist orders to account shutdowns for researchers they view as adversarial. But some of this shifted following the 2016 election. Public grievances over evidence that the Kremlin had fueled disinformation campaigns on social media, alongside revelations about stateside abuse of Facebook’s tools by Cambridge Analytica, led industry leaders like Meta and Google to promise reforms. Companies expanded their teams responsible for trust and safety—the work of enforcing platforms’ policies against violent threats, hate speech and disinformation.

But since 2021, the pendulum has swung in the opposite direction. Those same teams have been gutted as companies’ profits have fallen and political winds have shifted. And as the race to build generative AI has ramped up, major platforms including Meta, Reddit and X have walled off access to data they were once willing to share with researchers. Meanwhile, CEOs seem to be capitulating to right-wing lawfare against disinformation researchers—and even engaging in it themselves.

The remaking of Twitter has marked an especially dramatic turn for the industry. With Elon Musk now at its helm, X—a company that once championed its trust and safety operation but now runs a skeleton crew of platform integrity professionals—sued the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH) and Media Matters for America, after both nonprofit organizations published studies showing spikes in hate speech following Musk’s takeover.

The court saw X Corp’s case against CCDH for what it was. “This case,” wrote Northern California district judge Charles Breyer, “is about punishing the Defendants for their speech.”

Meanwhile, Musk has vigorously endorsed Donald Trump and frequently amplifies false narratives that support the candidate—something unimaginable for a social media platform CEO just four years ago.

Meta has changed its tune too, shedding staff and company initiatives aimed at promoting truthful information related to elections. In an August 2024 letter to Rep. Jordan, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg wrote that Biden administration officials had “repeatedly pressured” Meta to remove content related to Covid-19. “I believe that the government pressure was wrong,” Zuckerberg wrote.

Compiler sent multiple requests for comment to Rep. Jordan’s office and the House Judiciary committee. Neither replied.

A Pervasive Implied Threat

Researchers say the effects of these threats are permeating far beyond the courts and halls of congress. Rebekah Tromble, who runs the Institute for Data, Democracy and Politics at George Washington University, works with researchers and journalists facing intimidation and harassment. She says legal threats have upped the stakes for anyone doing public interest research focused on technology platforms.

“We all know that at any minute, [our work] could be taken up by actors with vested, particular political interests, and weaponized against us,” Tromble says.

Michelle Daniel, who recently left a senior role at the Global Disinformation Lab at the University of Texas at Austin, feels similarly. Any research on disinformation in the U.S., according to Daniel, is bound to trigger right-leaning media to submit an open records request. “You can be sure your private Slack messages will be dragged into the virtual town square,” she says. Daniel sees it all as part of a “general and creeping war on education.”

The risks weigh heavily on many scholars. “You realize that everything that you're doing is going to be misread and potentially used against you,” says Connie Moon Sehat, a co-leader of Analysis Response Toolkit for Trust, a public health information partnership between the University of Washington and the tech research group Hacks/Hackers. “So you have to think, how do I protect myself and my family when it gets to the personal stuff? How do I protect my team?”

“At a moment where the work we're doing is so important to share more widely with the public, doing that has become much much riskier,” Tromble says. “In fact, it's become dangerous.”

Legal threats, the loss of funding and the increasing lack of access to data has brought about a “perfect storm,” says Brandi Geurkink, who leads the Coalition for Independent Tech Research.

Last spring, the U.S. Supreme Court issued a ruling that brought some hope for researchers working in the field. The court rejected the plaintiffs’ claims in Murthy v. Missouri, the case that stemmed from the original lawsuit against Biden administration officials, including Nina Jankowicz. Many breathed a sigh of relief—a major threat to the work had been struck down.

Yet plenty of damage had already been done. Two weeks before the Murthy decision, the Stanford Internet Observatory had wound down much of its work on these issues, and several staff researchers, including DiResta, had stepped down from their roles.

DiResta noted that while the observatory’s critics focused on the misinformation aspect of the work, much of what the group did was to try to help the public better understand situations “in which the truth wasn’t yet knowable.” The public interest value of the research the observatory produced had, at one point, seemed beyond reproach.

“When a leading organization in a nascent, fragile field gets crushed and kicked aside by its sponsoring institution—in this case, mighty Stanford University—it has to have a deterrent effect on similar operations at other institutions,” says Paul Barrett, deputy director of NYU’s Center for Business and Human Rights. If Stanford’s observatory could fall, smaller, less well-funded organizations are likely to be even more intimidated, Barrett added.

Alex Abdo, who leads litigation efforts at Columbia University’s Knight First Amendment Center, was quick to point out that just like journalists, scholars’ rights to publish their research are protected under the first amendment. Regardless of their outcomes, Abdo sees the legal threats facing researchers as “cynical attempts to abuse our legal process for partisan ends.”

“Even a meritless or baseless investigation or lawsuit targeting these researchers will be successful in that political calculus, even if it doesn't result in a legal victory,” Abdo says.

Researchers are Fighting Back

In response to these lawsuits and congressional scrutiny, researchers are spending much of their time gathering documents to defend themselves from unfounded accusations, and less time actually doing their work. Tromble says it has caused some researchers to rethink their area of focus. But others are inspired to do this work precisely because of its social impact. “That type of researcher isn't as easy to scare off,” she says.

Securing funding for this type of work has become more challenging due to the political climate too. “Philanthropies are much more cautious than they were four years ago,” Jankowicz says. “They don't want to be dragged into the next political battle or hauled before Congress.”

“I definitely see less openness to sinking money into something that might be a frequent target for legal action,” Daniel says. But “politics is a pendulum,” she adds. “This downswing for disinfo researchers won't last forever.”

There is also increasing solidarity among those facing these challenges. “People are becoming more comfortable talking about what's happening to them,” says Geurkink. The Coalition for Tech Research has helped support mutual aid efforts, in which researchers who gain access to valuable data sets are finding ways to share them with other scholars.

And serious public policy solutions could be on the horizon. Senator Chris Coons’ Platform Accountability and Transparency Act, for example, would mandate that platforms share their data with independent researchers and the public, ideally allowing for scrutiny of their algorithms and content moderation decisions. In the European Union, the Digital Services Act aims to regulate large digital platforms to ensure a safer and more transparent online environment, in part by requiring companies to hand over data showing that they’re complying with the rules. Though that regulation applies only in Europe, researchers like Tromble hope it will have positive ripple effects across the pond. U.S.-based researchers affiliated with the Coalition for Independent Tech Research are already testing the regulation to see if they can use it to gain access to companies’ data once more.

But as we brace for the most contested election in recent U.S. history, legal protections for researchers remain elusive. GOP leaders continue to shore up the rhetorical power that positions them to do well in the court of public opinion, regardless of whether lawsuits convince sitting judges. And tech platforms appear reluctant to dart out and defend American democracy.

For NYU’s Barrett, it all makes for a grim outlook come November. “As we see academic and civil society analysts being intimidated, it flows toward the intimidation of election workers, it flows toward the incitement of right-wing activists using digital tools to try to knock out registered voters,” he says. “We've seen this film before…. It all happened in 2020. And we just barely survived.”

Ellery Roberts Biddle is a journalist and former fellow at Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society. She is currently co-authoring a book on the importance of independent audits for artificial intelligence systems.